Basic Academic

Essay Components

By Kelli McBride

Academic essay

writing is a specific type of writing that has its own rules and expectations.

No matter what your writing experience is, you must adapt to these rules and

expectations to get the best grade possible. My Composition/Rhetoric research

shows that most college classes require these basic elements. Follow the links

below to specific sections of this handout.

Document

Contents and Links:

|

Standard

academic English in a fairly high diction |

![]()

1. Standard academic English in a fairly

high diction.

If you cannot

communicate proficiently in English, grammar and mechanics, then no matter how

good your argument is, readers will find the mistakes distracting. Worse, they

may find your paper incomprehensible. Your LB Brief handbook, as well as a

variety of resources on the Internet, can help you correct the errors I point

out on your essays.

2. Structure:

Formal academic essays

are rigid in structure: intro, body, conclusion, thesis statements and topic

sentences.

In contrast, professional essays, many of the ones in

our textbook, will not always strictly adhere to a formal structure. In some

cases, readers may not even see a clearly written thesis statement, and people

will even disagree over what the point of the reading is. The purpose of

professional and literary writing is not always to present a clear argument.

Instead, it is often to provoke thought and discussion by leaving ideas open

ended. In academic essays, though, writers must present a clear thesis-driven

paper with the three-part structure, evidence to support the thesis, and an

awareness of persuasive appeals. These appeals comprise the Rhetorical Triangle

Aristotle called these

"pisteis." The 3 major ways we appeal to our audience are through logos,

pathos, and ethos. Logos is reason: common sense, facts, figures, and objective

data. I'm using information that I know will invoke an emotional response in my

reader, The author in making an argument uses research and word choice to

convince the audience by appealing to its logic and reason. This is the

preferred appeal in academic writing. Pathos is emotion. The author

uses empathy and sympathy to convince the audience by appealing to its

emotions, such as pity, fear, anger, patriotism, etc. Ethos is

credibility and trustworthiness. The author uses the credibility and ethics of

resources (which can include personal experience and the tone the author writes

in) to appeal to the audience by appealing to its trust. For more on classical

rhetoric, check out the following web pages:

o http://web.cn.edu/kwheeler/resource_rhet.html

o http://www.molloy.edu/sophia/aristotle/rhetoric/rhetoric1a_nts.htm

o http://www.rpi.edu/dept/llc/webclass/web/project1/group4/index.html#logos

o http://www.rhetorica.net/textbook/

If authors use the appeals illogically or dishonestly,

then they are guilty of propaganda and logical fallacies. We will cover these

in the second unit.

3. Audience:

The teacher is rarely

your audience in college classrooms. We are your evaluators, but not the group

that you are writing to necessarily. You must identify and target a specific

audience - know enough about them to make important decisions concerning

vocabulary, background information provided, types of examples to use, sources

to stay away from, and which rhetorical appeal to use.

what is my audience's education level? What words will

appeal to them or turn them off? For example, if I have a conservative audience

and I label something liberal, I will probably distance that audience. Instead,

I need to find another way to describe it that won't get a knee-jerk reaction.

what does my audience already know about this issue?

What do they NEED to know to be able to understand the argument I'm making? Be

sure you provide only necessary relevant info - don't stuff your

introduction, or your essay, with trivial facts or biographical information

that does nothing to further your argument.

what will appeal to my reader - anecdotal evidence?

Statistics? Hypothetical examples? Examples come in 3 types: 1) specific: you

are giving the reader an example of a real person or real event (e.g., Tommy

drives home from work in rush hour every day, and this adds to his stress). 2)

Typical: you are painting a picture that is a composite of what usually occurs,

but not citing specific people or places (e.g., Many residents of Shawnee drive

home from work in rush hour every day, adding to their stress). 3)

Hypothetical: you are playing the "what if" game to show people what

might happen or may have happened because there is no specific evidence

available (e.g., If Shawnee residents drove home from work in rush hour every

day, their stress levels would increase). You would use this last one when

speculating about the effects that something might have, or when trying to

figure out what may have occurred. No one type is better than the other because

it all depends on the situation and the audience. You do need to use specific

evidence in academic essays at some point, but you have some wriggle room.

Again, what will turn off your reader? Consider a

paper on qualities of a great leader. If I cite Hitler, then automatically, no

matter how valid the info that I'm using from him, I will get a negative

reaction from most reader. If I am writing about the qualities of great leaders

according to Machiavelli, who famously advised princes that they should

encourage fear rather than love in their followers in order to maintain

control, then citing Hitler is completely reasonable. I’ve added a context,

Machiavelli’s definition, that would make the choice of Hitler obvious rather

than potentially racist. My audiences personal profile (including politics,

culture, religion, age, gender, and geography – just to name a few), may

require I rethink exactly who I will use to support my thesis, the types of

examples I provide, and even the diction, tone, and style I use in my writing.

To ignore the audience is to make my ethos vulnerable. Of course, may arguments

target a general audience who are bound together simply by a common interest in

the issue, a common nationality, or something else.

4. Context:

What is the situation

that I'm creating in which to argue my point? We rarely argue topics in a

vacuum. Instead, we must connect them to something the audience will see as

relevant. That could be time, place, ideology, etc. For example, a discussion

of tuition hikes as Harvard will not likely be interesting to an SSC audience.

However, if the writer connects what is happening at Harvard to changes in

Oklahoma higher education, then suddenly that tuition hike is relevant and more

interesting. Time can also be an important context. No one can

write a paper that talks about “since the beginning of time” or “since the

first human appeared” because that is simply too large a time frame to cover,

and no one knows what was really going on then. However, I can limit topics by

choosing specific time contexts. A discussion of civil liberties in America

would be very different if I choose to look at the 1990s

as opposed to the post-9/11 era. My audience might also provide a variety

of limiting contexts. Perhaps I want to use the Christian Bible as part of my

reasoning for supporting legislation. Religious freedom makes it impossible to

justify that legally to general audience. However, if I limit the audience

context to Southern Baptists (and specify that in my introduction), I can

reasonably expect them all to acknowledge the Bible as a guide to ethics, from

which most laws spring. The fact that all of your essays must follow

standard Academic English provides an important context that you must

incorporate in your writing. Context will be different for every essay.

Essay Writing: The MEAT Method

Overview

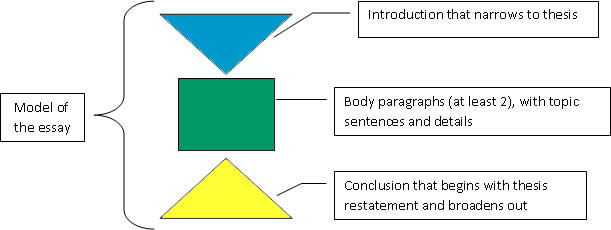

An

academic essay is a group of paragraphs, organized into three sections. Those

sections are: introduction, body, and conclusion. These sections may have more

than one paragraph in each, though the body section must have more than one

paragraph. Body paragraphs differ in structure and function from introduction

and conclusion paragraphs, so we will study each section separately,

identifying the common characteristics in a traditional academic essay. Using

the MEAT method, we can write well-developed (dare I say “meaty) paragraphs.

MEAT stands for: Main point – Examples and Explanations – Analysis

– Transitions.

An

essay has two layers of main points: the thesis and the topic sentence.

this is the overall point of the essay, and you derive all topic

sentences from the thesis. The thesis statement should have two major

components: the subject and the purpose. The subject announces what the

essay is about, and the purpose announces what you are going to tell us about

the subject. You can also provide an “essay map” in your thesis. This

means previewing the topics in each body paragraph.

Example thesis: Though Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr. provided

important leadership during the Civil Rights Movement, King’s leadership style

proved more appealing to the mainstream who sought integration for America not

more segregation.

·

Subject: Contrasting Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr. as

leaders during the Civil Rights Movement.

·

Purpose: Show how Martin Luther King, Jr.’s

style of leadership appealed to those wanting to integrate rather than

segregate.

·

Audience: People interested in diverse leadership styles of the

two and why one spoke to a wider audience.

Another way of thinking about the thesis is more mathematical,

what I call the

“Thesis Equation.”

Note: a thesis statement does not always include Z and {a, b, c}, but

it should always have an X and Y. However, your essay must always make clear

what the Z and {a, b, c} are to the reader. Z begins in the introduction and

continues throughout the essay in the choice of reasons to suit the audience

and context as well as the tone and diction levels. {a, b, c} come directly

from the X/Y statement and the Z because they are reasons that logically

support the essay’s thesis and also will appeal to the essay reader.

Example: Students should not complain about tuition hikes at

Seminole State College because the money provides many useful services to them

in computer labs, the library, and in classrooms.

|

X

|

= |

SSC

tuition hikes |

|

Y |

= |

students

should not complain |

|

{a, b, c} |

= |

money

provides services in computer labs, the library, and in classrooms |

|

Z

|

= |

the

limiting factors are: students (the audience and complainers) and SSC (where

the tuition hikes are occurring) |

Thesis statements are not:

o Statements

of fact: SSC raised tuition this year.

o Statements

of the obvious: Students don’t like paying tuition.

o Announcements of

intent:

This essay will explain how SSC uses tuition money in ways beneficial to

students.

These drive the body of the essay. For each specific point you

make to support your thesis sentence, you must have a topic sentence and at

least one body paragraph that provides detailed support. For the thesis on King

and Malcolm X, the topic sentences must come from the aspects of leadership you

have established as important for this discussion. You must do that in

your introduction, before you announce your thesis. You must tell your

reader why this is an important discussion to have – why should we analyze

these two? How are you defining leadership in this context?

Sample Topic sentences:

· Martin

Luther King, Jr. lead his supporters into any conflict by first teaching them

how to maintain a peaceful attitude that would not provoke or justify a violent

response from police.

· Malcolm

X encouraged aggression in his followers.

Topic sentences have two parts: the topic and the attitude.

The Topic: The topic of a paragraph is a word or

phrase that the author has narrowed down. By “narrowed down” I mean that the

author has found a topic that he can cover effectively in one paragraph.

Instead of “tuition costs,” I might write about “SSC tuition hikes.” Authors

narrow topics with prewriting techniques, such as brainstorming, freewriting,

and clustering. These techniques ask the writer to jot down as much as possible

about the topic. These prewriting techniques have multiple purposes:

o They

clear the author’s brain

o They

allow the author to get down, on paper, everything he knows about a topic

o They

allow the author to begin organizing information through grouping of like

information and deleting of irrelevant information

Choosing a particular prewriting

technique depends on the author and the purpose. Some techniques lend

themselves to more detailed information, and others appeal to particular

learning styles. Authors should practice using several techniques and

discovering which work the best for them under certain circumstances.

Prewriting might yield the following topics on “tuition costs:”

o

Recent hikes in tuition at SSC

o

Breakdown of tuition use at SSC

o

Comparison of tuition at SSC and other area colleges

o

Getting financial aid at SSC

Notice that all of these topics deal

with SSC. This is another way of narrowing a topic – adding a geographical

CONTEXT. Since tuition may change from school to school, an author cannot

easily make a blanket statement about tuition in Oklahoma or America. The more

he can narrow the scope of his topic, the more he can accomplish in the

paragraph. This, however, is only half of the topic sentence. At this point,

the author has not informed the reader what he will say about the topic. This

is the “attitude.”

The Attitude: Before a writer

has a topic sentence, he must figure out what attitude he wants to take. We can

take the four topics above and add attitudes to them:

o

Recent hikes in tuition at SSC + will prevent many current SSC

students from continuing their education.

o

Breakdown of tuition use at SSC + reveals the college’s commitment

to providing advanced technological resources for students.

o

Comparison of tuition at SSC and other area colleges + shows the

great bargain offered to students attending Seminole for their first two years

of college.

o

Getting financial aid at SSC + can be easy with the right

planning.

Now we have a complete topic sentence for the paragraph. Writers

must be careful that they do not begin a paragraph with simply an announcement

of a topic rather than a complete statement of purpose: topic + attitude.

After the author has settled on a topic sentence, he can begin planning

his paragraph. Planning is an important part of writing. When a writer

has some idea of where he’s going with his paragraph, he can better prepare for

any obstacle to his position on the topic that he might face and/or that the

reader might have. Obstacles can present themselves in several ways:

o Lack of basic

knowledge of topic: the reader does not know enough background information to

fully appreciate or understand the author’s point.

o Different opinion

about topic: the reader has an opposing position and may strongly disagree with

the author or challenge the author’s evidence and reasoning.

o Different

education level than author: the reader may not have the same vocabulary or

educational background as the author, so the author must modify his diction and

style to suit his audience.

o Difficulty

finding evidence: the author may not find or have trouble finding the facts and

examples he needs to prove his position on the topic.

Even the best planning might not help the author prevent some of

these problems, but it helps lower the odds of major problems late into the

writing process.

Explanations and Examples:

Following

the topic sentence, you must explain your point to your reader. What does

it mean when you say that King taught his followers how to respond? What does

“aggression” consist of concerning Malcolm X’s methods? Without this

explanation, your reader may not understand the specific point you are trying

to make. Explanation would also include important definitions: any words or

terms the reader may not know, or that have potential multiple means that the

reader may misinterpret. Explanation usually remains at the general level. You

discuss what was the overall behavior like. To fully explain, you must also

provide readers a specific example to illustrate your explanation. In

this case, you could use a common knowledge incident or cite (and document)

from a source that shows King’s methods. If necessary, you might even present

two or more examples to show a variety of techniques or to prove that this was

the dominant method. Examples also provide evidence to support your point. If

the topic warrants, the author must back up his position with facts,

statistics, authoritative testimony, and other objective evidence that supports

his attitude on the topic. The more debatable or argumentative the attitude,

the more likely the author will need objective evidence outside his own

experience or opinion.

Analysis:

Just

providing materials for the reader is not always enough to make our case. The

writer has to tie them all together by analyzing what they mean, what their

significance is, why the reader should be concerned or pay attention, etc.

Analysis can also provide evaluation (e.g., which is the better choice) and

synthesize two ideas to form a new concept or present a new perspective. Often,

academic argument asks students to read a source, like a literary or

philosophical text, and make a connection to current events. The author’s role

is to synthesize the different elements by providing a context that connects

them. For example, if I have to write a paper that justifies Hitler as an

excellent leader, how can I connect these two ideas (Hitler + excellent leader)

in a way that makes sense to most ethical people today? By using Machiavelli’s

definition of an excellent leader in his book The Prince, I can

make a logical argument. You will use this technique in this class. I will

provide the text and a context (such as Plato’s “Allegory of the Cave” and a

modern issue), and you must synthesize the two.

Transitions:

between

each component, you must provide connections that help the reader see the

relationship between these parts, like cause, effect, comparison, and contrast,

etc. You simply don’t list these elements in order. It is up to you to provide

the coherence and unity through transitions that logically guide your reader

through your reasoning.

As

you continue to work on your essays, print out a clean copy and mark each of

these items on your draft. If you are missing any one, then you should

work on adding that component to your paper. If your essay is falling short of

the required length, chances are you are missing some of these components.

SAMPLE ESSAY with LABELED PARTS

Essay components |

Just Say "No" to Joe |

|

Introduction that starts broad and narrows

to thesis; provides background information and context for essay. |

This

organization today faces many challenges. One of the crucial decisions that

members must make is setting five-year goals. For this, the directors must

appoint a chairperson for the development committee. This position requires

someone who can work well with others, provide responsible leadership, and

consider suggestions from other members of the committee. |

|

Thesis statement |

Though

the directors are considering Joe Smith for this position, they should not

appoint him as committee chair because he exhibits none of these crucial

qualities. |

|

First body paragraph: opens with intro sentence that isolates

one part of the definition from the previous paragraph and adds more

specificity. |

New paragraph: The chair

must be able to work with a variety of people within the organization and

outside of it. At times, the chair will encounter people who are of higher or

equal rank, and he/she must be able to adjust to these different situations. |

|

Topic sentence: reason that supports thesis |

However,

Mr. Smith only likes to work with people he can dominate. |

|

Evidence that develops topic sentence and proves author's point |

For

example, last year, he chaired the festival committee and managed to anger

the president of both town banks, the president of the chamber of commerce,

and the assistant to the event’s keynote speaker, not to mention the many

organization members to which he was rude. An inquiry into the many

complaints revealed that Mr. Smith was unable to respect the authority of other

people and always wanted to be the top dog. A similar problem occurred when

he was in charge of the 2002 Charity Drive and the 2003 Christmas Auction and

Dinner. The organization received many letters and phone calls complaining of

his highhanded manner. |

|

Summary of paragraph |

This

is hardly the quality of an outstanding development chair. |

|

Second body paragraph: opens with intro sentence that isolates

one part of the definition from the intro paragraph and adds more

specificity. |

New paragraph: The person

heading the committee must show responsible leadership. This involves giving

credit to everyone involved in successful ventures and shouldering the

responsibility for any problems that occur. |

|

Topic sentence: reason that supports thesis |

Mr.

Smith, though, likes to take credit for any success but blame others for

failures. |

|

Evidence that develops topic sentence and proves author's point |

Two

years ago, the Charity Drive raised more money than in the 2000 and 2001

seasons combined. This was the result of a team effort and the work of

Lindsey Beresford who arranged for Reba McIntire to be the keynote speaker.

However, Mr. Smith took credit for these accomplishments and never mentioned

any other member of his team or Mrs. Beresford's contribution. Yet, a year

later, when the keynote speaker backed out at the last minute because Mr.

Smith failed to confirm the date of the festival, he refused to acknowledge

his fault and instead let people believe that it was a team failure. No one

on either of these committees will work with Mr. Smith because of the ill

will he built. |

|

Summary of paragraph |

The

organization does not need a chair who will drive people away. It needs

someone who provides strong leadership and draws in people. |

|

Third body paragraph: intro sentence with last definition |

New paragraph: Finally,

the chair should encourage all team members to participate and submit ideas

for developing the organization. Having many talented minds working together

will create a stronger future. |

|

Topic sentence: reason that supports thesis |

Here

again, Mr. Smith has proven that he cannot accept input from anyone else. In

fact, he sees any suggestions at odds with his own plans as challenges to his

authority. |

|

Evidence that develops topic sentence and

proves author's point No summary of paragraph |

This

year, he proceeded to implement his own plan for streamlining the yearly

membership drive. One of his committee members had previous experience in

this job and offered advice that would improve Smith’s plan and make the

system more efficient. Mr. Smith ridiculed this person in front of several

members and refused to listen to any of his ideas. The result was a

catastrophe. The new plan cost the organization twice as much as the old

plan, and in the process of implementing it, Mr. Smith lost several years

worth of computer records that support staff had to later re-type. This took

seventeen hours to finish. The person Mr. Smith ignored suggested a complete

system backup to prevent such loss and cost-saving measures that would have

saved money. |

|

Transition and summary of essay/ Restatement of thesis |

New paragraph: Mr.

Smith's record speaks for itself: he would make a very poor committee chair. |

|

Conclusion gradually broadens by summarizing points,

establishing why issue is important in author's point of view, and calling

for action from directors. |

The

directors cannot afford to give him any more opportunities to antagonize and

belittle members, waste money, and take this organization down the wrong

path. This position is too important to organization’s future to put in the

hands of someone who has very little concept of teamwork and leadership.

Other members have much more experience and have proven that they have the

necessary qualities to chair this committee. The directors should consider

them instead of Joe Smith. |